The Viking Factor

Among the most immediate pressures came from the north. In the mid-9th century, Viking raiders—Danes, Norwegians, and Swedes—descended upon the coasts and rivers of West Francia in longships. They plundered monasteries, burned towns, and overwintered in fortified camps. The kings of West Francia were often powerless to stop them.

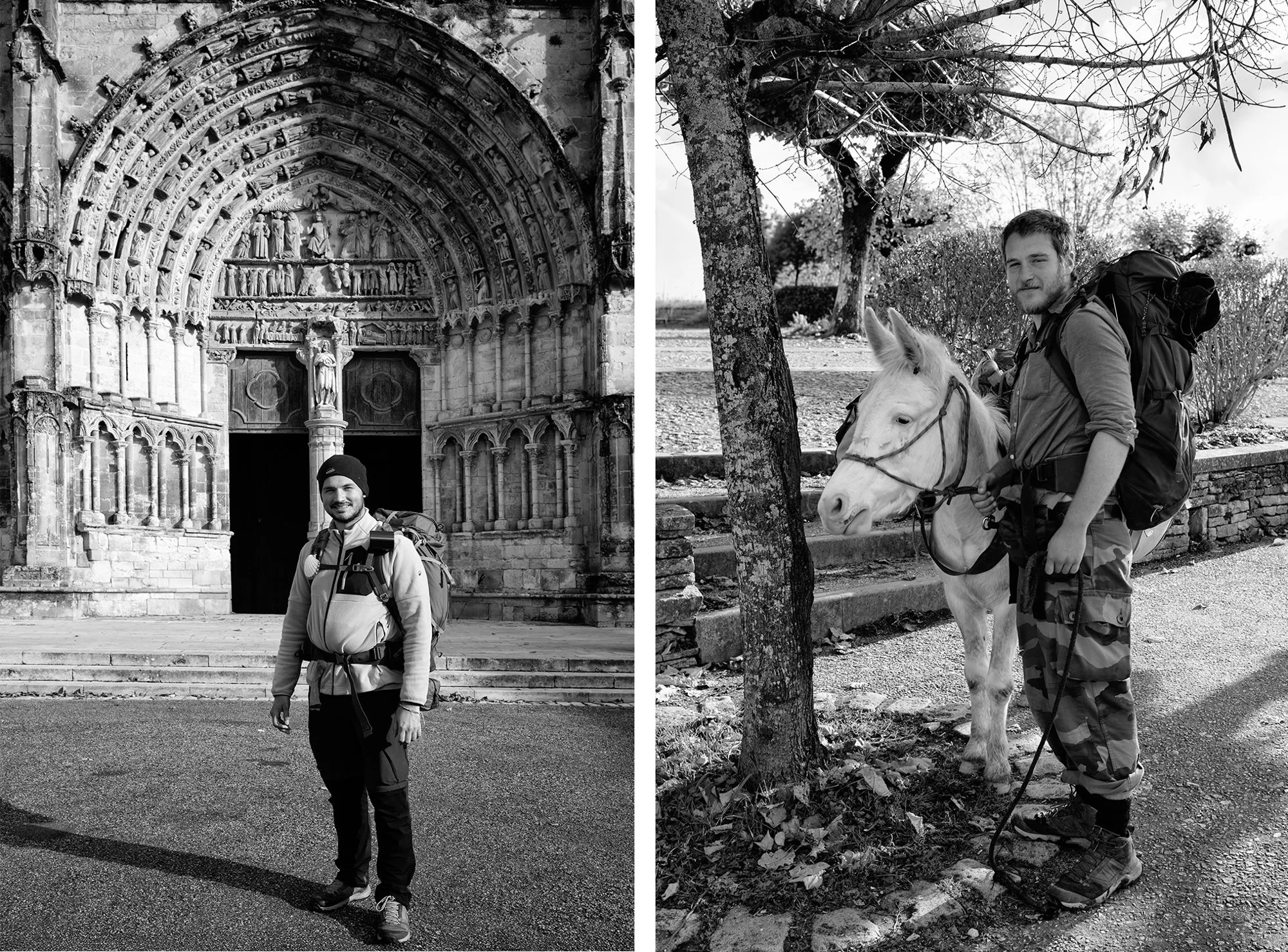

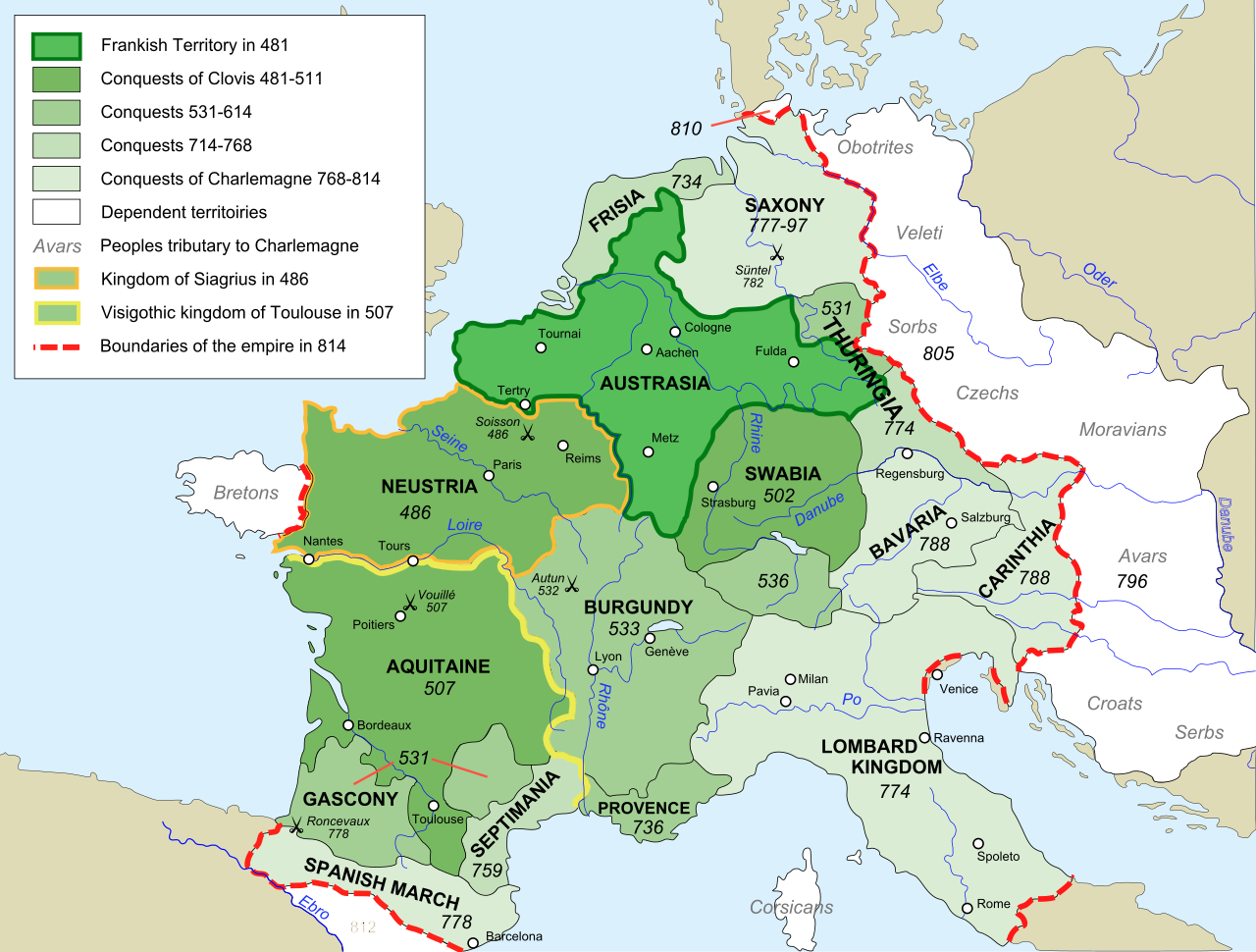

Rather than wage endless war, King Charles the Simple struck a deal. In 911, he granted land around the lower Seine River to the Viking chieftain Rollo, on the condition that Rollo convert to Christianity and defend the region against future raids. This land became the Duchy of Normandy. Its rulers—originally Norsemen—would become some of the most formidable lords in all of France.

By 1035, the duchy was thriving. Its duke, Robert I (called the Magnificent), had gone on pilgrimage to Jerusalem, leaving his illegitimate son William—still a child—in charge. That boy would become William the Conqueror, and his future conquest of England in 1066 would tie France and England together in centuries of dynastic entanglement.

The Rise of the Feudal Lords

As Normandy emerged, so too did other regional powers. In the southwest, the Dukes of Aquitaine governed vast lands, stretching from Poitiers to the Pyrenees. Aquitaine was culturally distinct, with its own dialect and customs, and its rulers acted with near-total independence.

In the northeast, the Counts of Flanders dominated the economic life of the region, trading with England and the Low Countries. In the center of the kingdom, the Counts of Blois controlled key cities like Chartres, Tours, and Troyes—forming a buffer between the royal domain and the Champagne plains.

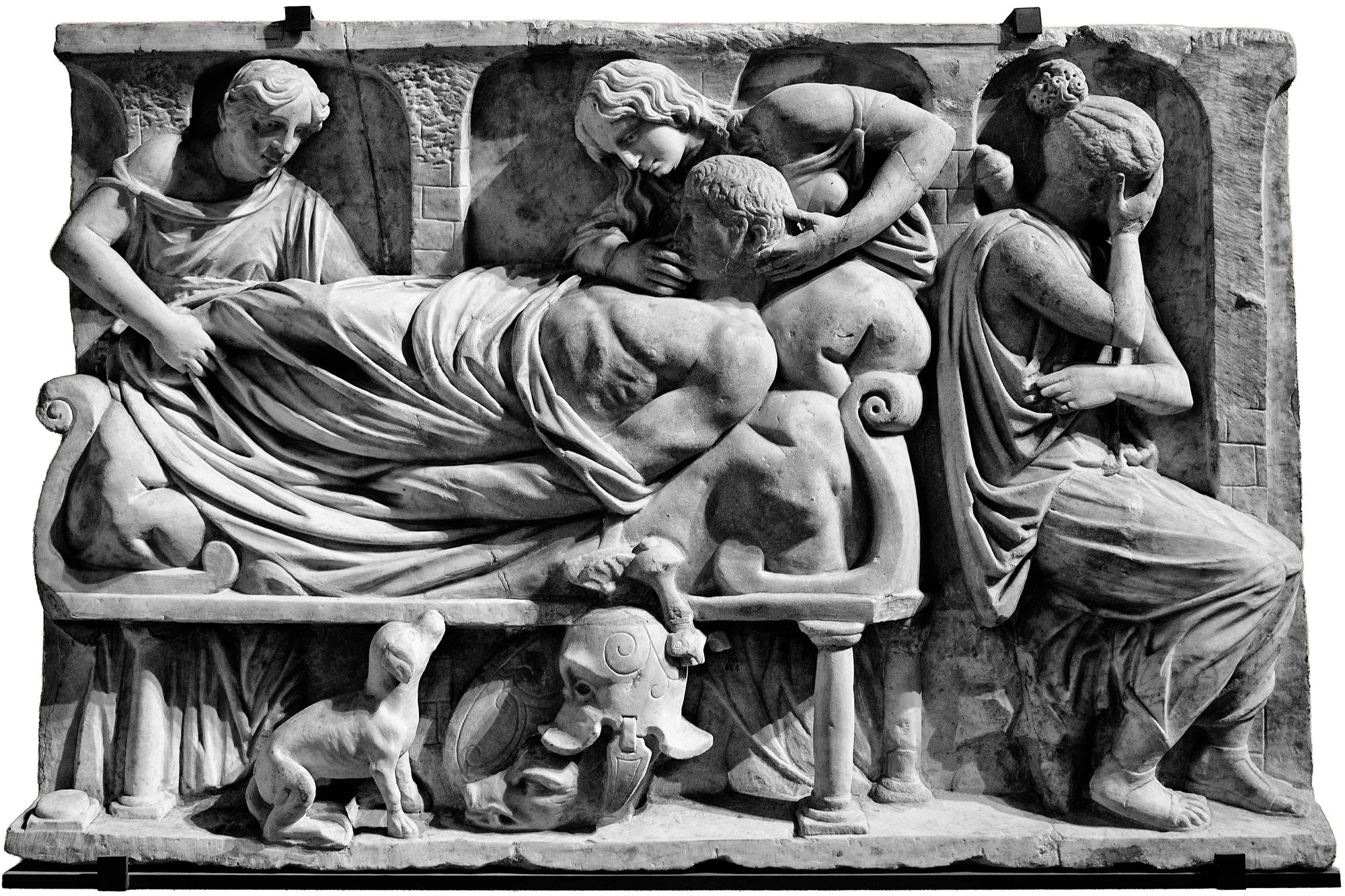

And in the rugged land of Anjou, Fulk III, known as Fulk Nerra or Fulk the Black, carved out a reputation as one of the most brutal and effective warlords in France. A brilliant tactician and relentless castle builder, Fulk waged war on his neighbors and expanded Angevin influence across western France. In 1035, he was still alive, nearing the end of his long reign, and preparing to hand power to his son, Geoffrey Martel. This family line—the Angevins—would later give birth to the Plantagenet dynasty, which would rule England and much of France in the 12th and 13th centuries.

A Weak but Persistent Monarchy

All the while, the Capetian kings clung to power. In 987, following the death of the last Carolingian king, the crown had passed to Hugh Capet, Duke of the Franks. Though his election was the beginning of the longest continuous royal line in European history, it was a fragile inheritance. Hugh, and his son Robert II, held sway over only a modest royal domain. Their influence did not extend far beyond the Île-de-France.

By 1035, Henry I had just taken the throne after the death of his father, Robert II. Young and untested, he faced a kingdom dominated by barons who owed him homage in theory, but in practice governed independently. France had a king, but little centralized state.

1035: A Fractured Realm

So what did France look like in 1035?

It was a land of lords, not a unified state. The king ruled in name, but dukes, counts, and bishops wielded true authority. Some were descendants of Carolingian officials; others were former Viking raiders. Local customs, languages, and loyalties often mattered more than the distant king in Paris.

But though fragmented, this was also a time of innovation. Feudal bonds created webs of mutual obligation. The Church expanded its influence, promoting peace and education. Castle-building transformed warfare and society. And the seeds of future conflict—between kings and vassals, between France and England—were being planted.