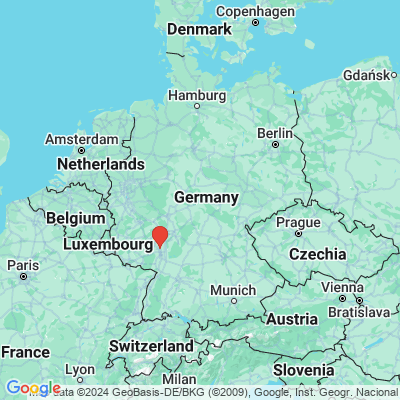

A playground in Dinkelsbühl (Germany).

Walk through a German town on a weekday morning and you might notice something striking: the playgrounds are pristine, imaginative, and meticulously engineered—yet often eerily quiet. Germany, like many Western European countries, faces a persistently low birthrate (around 1.3–1.5 children per woman in recent years).

Over decades, fewer births mean shrinking school classes, a tightening labor market, and mounting pressure on pension and health-care systems. With a smaller working-age population supporting a growing number of retirees, the classic social contract of “today’s workers fund tomorrow’s pensions” becomes fragile. Immigration softens the trend but does not erase it.

Ironically, the few children who are born may enjoy the best playgrounds in history. German municipalities, proud of their Spielplätze, invest in elaborate wooden climbing castles, rope pyramids, and water-sand labs that would make many theme parks envious. Safety standards are exacting, and design competitions fierce.

The result? Superb public play spaces—often half empty. It’s a gentle, almost humorous side effect of demographic change: as the child population shrinks, the investment per child soars.

Behind the quiet slides lies a serious challenge: how to sustain economic vitality, care for an aging population, and keep intergenerational solidarity alive. Germany’s situation is emblematic of much of Western Europe, where prosperity and lifestyle choices have combined to bend the population curve downward.

For now, the next time you see a state-of-the-art climbing tower standing still under a perfect blue sky, remember: it’s more than playground design. It’s a silent symbol of a continent rethinking its future.